Modernism was king when I went to architecture school back in the late 90s and early 2000s. And the architect’s ego was carefully cultivated through very severe critiques of student work which quickly established who the stars of the class were and who the laggards were. Architecture was all about what we created and how we could impose our vision on the natural world. Professors blathered on with great delight about architects like Le Corbusier and Oscar Niemeyer. These were architecture’s heroes. Nevermind that their urban planning proposals had little to do with the actual human experience and everything to do with their top-down vision of how people should live.

The The Timeless Way of Building by Christopher Alexander was not on our reading list in architecture school. And now I know why. The book turns on its head almost everything I learned in school and goes even so far as to imply that there is no real need for architects at all.

Besides being an author and a teacher, Alexander is himself an architect. But he took a circuitous path to the profession and first studied chemistry, physics and mathematics at Cambridge. He got a Bachelor’s in Architecture, a Master’s in Mathematics and got a PhD in Architecture from Harvard. While getting his PhD, he studied transportation theory and computer science and at Harvard worked on cognition and cognitive studies.

Alexander’s love of math and science comes through in his work on architecture. The building block of his theories is something he’s coined a “pattern language”, which is a series of rules associated with any building endeavor including everything from the hinges of a door to entire cities. The pattern language is something that Alexander believes is at the root of “the quality without a name”. It is what allows people to build structures with this nameless and almost divine quality.

He goes to great lengths to define this “quality without a name” but ultimately concedes that it is undefinable and can only be spoken of in such terms as “alive”, “whole”, “comfortable”, “free”, “exact”, “egoless”, and “eternal”. But even these descriptors fall short and in essence Alexander says that a built structure with the “quality without a name” becomes indistinguishable from nature and indeed becomes a part of it.

In The Timeless Way of Building, which is his first book in the six-volume Center for Environmental Structure series that also includes A Pattern Language: Towns, Buildings, Construction and The Oregon Experiment

, Alexander painstakingly builds his argument about a single way of building that is in harmony with nature and has nothing to do with ego. He first begins by defining elements and then the relationships between elements, which ultimately make up patterns. He asserts that just as there are discernible patterns in nature, such as in the ripples in a patch of wind-blown sand, there are natural patterns in the built environment too. And these are the patterns that Alexander sets out to define in this and his subsequent book, A Pattern Language, so that everyone, not just architects, have the tools and the “language” they need to build structures with “a quality without a name”.

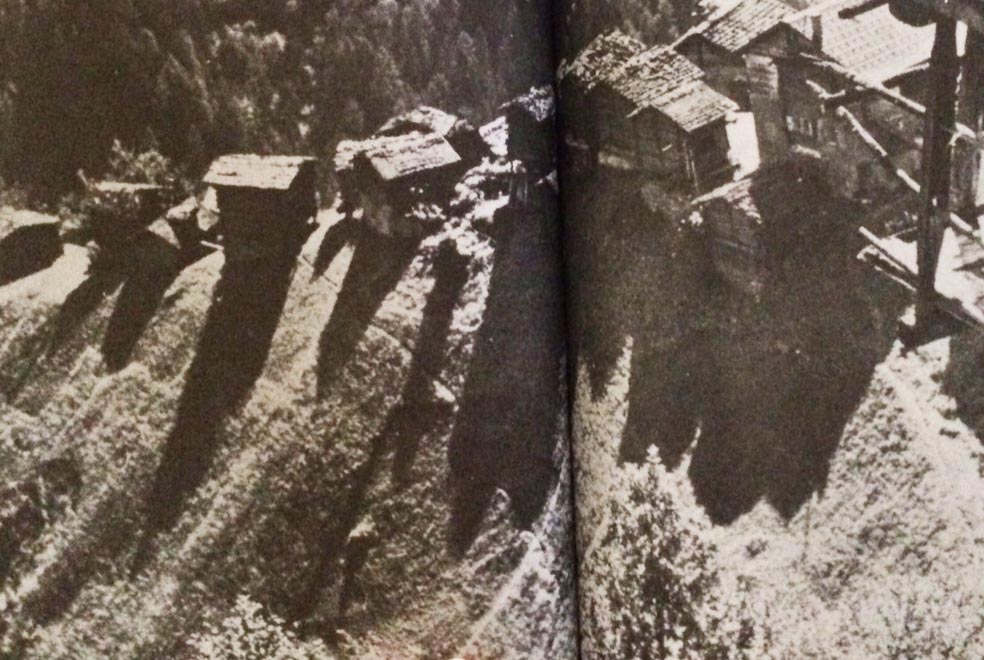

An example in the book of a pattern language is that of the stone houses in the south of Italy. The pattern language consists of a 3 meter square main room, two step main entrance, small rooms off the main room, arch between rooms, main conical vault, small vaults within the cone, whitewashed top to the cone, whitewashed front seat. Each of these elements contains a myriad of patterns within itself. It is almost as if you can discover patterns as far down in scale as you want and as far up in scale as you want. In other words, the pattern “square main room” is itself composed of several patterns, which are also themselves composed of several patterns and so on. This “language” can generate an infinite variety of combinations and outcomes which all fit within the general definition of “stone houses in the South of Italy”.

As you can see, the idea of a pattern language can get rather complicated. But that is the last thing Alexander intends it to be. For him, patterns already exist and they are just meant to be discovered and then adhered to. Things want to be built a certain way and it is up to the builder to determine what that is.

The key is not to think about it all at once, Alexander says, but instead start with a singular element, like the front entrance, for example. Figure out where, what size, what materials, what scale and so forth it wants to be and then move on to the front room. Of course it’s probably wise to begin with the site pattern first, to determine how big you want your structure to be, where you want it to sit on the site, and what general shape it needs to take to respond to climate and site conditions.

Essentially, he implies, everything is already designed. And perhaps he implies that everything is already designed by God or the Divine. Just like an acorn has the blue print in its DNA to grow into a tremendous oak tree, our built environment has built-in blueprints as well, poses Alexander. And these are the pattern languages that he’s set out to define. Our job as mortal builders is to discover what that these patterns are and then to build according to their instructions.

But when everything is already designed as it “should” be, then it leaves no room for an architect’s will, or his ego. And that is just as it should be, according to Alexander. He derides Modernist architecture precisely because it is so centered on a single person’s ego. He says that modernism was one of the movements that killed pattern languages, and perhaps killed architecture. Modernism is the product of a single architect’s vision which is imposed from the top down. The people that actually occupy modernist buildings and modernist cities have no idea what language the architect is using. Nor does the modernist language resonate with them and their everyday lives. It is foreign to them. They become victims to someone else’s vision for what their town should be. Take the city of Brasilia, for example, which was designed by modernist architect Oscar Niemeyer. The city is composed of high-rises that surround huge open spaces. It completely lacks a human scale and people who live their report feeling isolated. How a space feels is the ultimate measure of a good space for Alexander. If a space feels good it must have the “quality without a name”. If it doesn’t feel good, it’s not built right.

This book is essential reading for all architects, even though Alexander’s theories are not generally accepted within contemporary architectural discourse. Ideally this book should be read by everyone, but it is a difficult read. It becomes very esoteric and a little tedious when Alexanders devotes chapter upon chapter to the development of specific patterns. Delving into specific patterns is also where it becomes most suspect to me. While reading about specific patterns that Alexander laid out, I noticed that my mind kept rebelling at those patterns, thinking, well that’s not always true, and what about this circumstance and that? For example, in his pattern Network of Paths and Cars, Alexander asserts that people need some measure of separation from cars for safety but they also like to “be where the action is” and that is where cars are. But this doesn’t explain the extremely successful and populated streets that have been closed to cars and now pedestrian only. Some of the things that Alexander asserts almost as “universal truths” don’t ring true to me.

Also, when these specific patterns are developed, it doesn’t leave room for change and evolution. He mentions the patterns of freeways quite a bit in the book and how they’re positioned in cities. But what if you want to get rid of freeways? Does having a pattern language that is passed down from earlier generations allow for this kind of evolution?

The most interesting, captivating and convincing parts of the book include when he first discerns “the quality without a name” and then goes on to talk about how every built element has a way it wants to be built according to it’s location, the culture and routines of the people who live there, the available materials in the region and a host of other factors.

The idea that a built structure is exclusively the product of its “inner forces” – which are all the things that affect it – is revolutionary in contemporary architecture. In school, we learned that context was important to a building project but that it was just one factor of many that went into the design of a building.

But Alexander’s complete surrender of the built environment to its “inner forces” is unheard of and something that threatens the very existence of architecture today. His philosophy that anyone can build buildings and cities in the best way possible and that contemporary architects actually detract from the quality of buildings and cities is extremely threatening to the practice of architecture today, which exists on the premise that architects are the only ones who know how to design a building.

Though I wasn’t completely convinced about the actual specific patterns that Alexander lays out in the book, I am convinced that each building project and each building element has a very specific way it wants to be. And when it is built in this fashion that it does, indeed, feel good to inhabit. It feels alive and full of “the fire” that he talks about. And when it is not built in the way it wants to be built, something feels a little off-kilter.

One way to bridge contemporary architecture and Alexander’s theories is perhaps to make architects the facilitators of discovering what that way is. What is the way your house wants to be built? What is the way your office building wants to be built? What is the way your corner store wants to be built? Perhaps discovering the innate qualities that dictate a well-built project can be the task of architects. And perhaps they can then carefully and diligently record and share these patterns so future generations of people can rebuild and repair and build anew in the timeless way of building.

Photo credit: Photographed by the author from an image in book The Timeless Way of Building, New York Oxford University Press, 1979.