Yesterday, I attended a wonderful museum bike tour where we visited the Oregon Nikkei Legacy Center that displays the history of Japanese internment camps in Portland. And later we visited the Oregon Historical Society, and saw the All Aboard: Railroading and Portland’s Black Community exhibit, which is running through April 21st.

As we looked through these exhibits of past acts of discrimination that Oregon committed, including institutionalized segregation, there was some discussion as to how it’s had a ripple effect to today. One person joked that it’s hard to tell that Oregon isn’t segregated today, as Portland is so white.

Yesterday’s educational tour about Portland’s racial and ethnic past reinforced my curiousity as to why Portland is so white today. A couple of weeks ago, I began an investigation based on Carl Abbott’s book,Portland in Three Centuries, the Place and the People, and published Part I of the Story of African Americans and Other Nonwhites in Portland. Below is Part II of that story:

Before WWI, the majority of Portland’s 1000 blacks lived between Burnside, Glisan, Third and Fourteenth Avenues because these areas were close to hotel, restaurant and railroad jobs. By the end of the 30s, the census counted 2000 black residents with more families than single men. By 1940, more than half of the city’s African American’s lived in Albina, where inexpensive older housing allowed widespread home ownership.

But unlike the European immigrants who lived in these areas before, African Americans experienced a “deeply embedded racial discrimination,” according to Abbot. In a practice called Redlining, realtors conspired to confine home sales to certain blocks in Albina. Unions barred black members. Major hospitals admitted black patients but refused to hire black nurses. Trade schools did not admit black students. Portland, writes Abbott, was more racist than LA or Seattle.

During WWII, Portland’s African American population increased from 2100 to 15,000. Little private housing was available for single black men or black families outside of the Albina neighborhood. Neighborhood groups raised large protests at every rumor of African Americans moving into their areas. Most newcomers during the war had to live in defensive housing projects in Portland or Vancouver where they were effectively segregated from white Portlanders. The Housing Authority denied this institutionalized racism, but nonetheless steered thousands of African Americans into certain neighborhoods and buildings.

By the end of the war, a pop-up city called Vanport housed 6,000 African Americans. Vanport provided Portland a convenient place where African Americans could be isolated from the rest of the city. But on May 30, 1948, Columbia River flooded and wiped out the city forcing African American residents to crowd into Albina. People in the city were not welcoming. In 1950, the city passed a nondiscrimination ordinance for public accommodations, but voters repealed it. As late as 1955, Redlining continued among Portland real estate professionals.

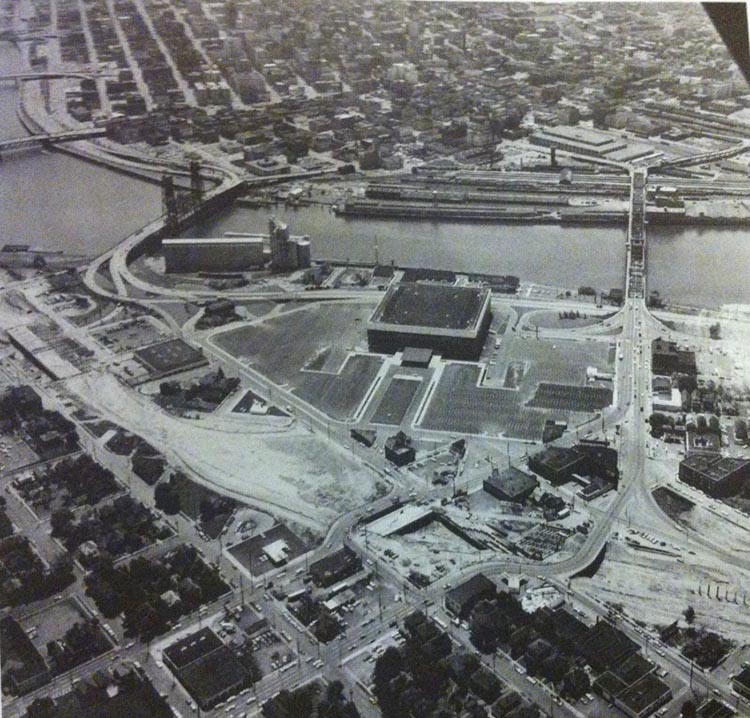

In 1960, the homes of hundreds of African American families were leveled on the east end of the Broadway Bridge in Albina due to the construction of the Memorial Coliseum. Along with the construction of the I-5, the Coliseum wiped out the heart of Portland’s African American neighborhood. The Coliseum and its parking lots replaced nearly 500 houses and apartments in Albina. Gone too were the fraternal lodges, and jazz clubs that had thrived in the 1940s and 50s.

In 1966, as part of the federal Model Cities program, the city picked a set of North and Northeast neighborhoods with large African American populations to become models of revitalization. A resulting plan in 1968 spoke openly about racial discrimination in a city whose white leaders denied having a race problem. The city council took 4 months to adopt the plan, which launched a 5-year neighborhood improvement effort that would improve social services and build community leadership in the North and Northeast neighborhoods.

In the 1970s, the first citywide victories for African American politicians took place. Charles Jordan won a city council appointment in 1974 and 1978. Gladys McCoy was the first African American to win a Multnomah County Commission seat in 1978.

In 1980, greater Portland’s African American population grew to 32,000 constituting 3% of the population, followed by Asians at 2% and Latinos and Hispanics also at 2%. In the mid-1990s, housing prices west of the Willamette went up, leading the white middle class to move into the working class neighborhoods east of the river. This newfound popularity of the east inner neighborhoods had the effect of displacing the lower-income households, mainly African Americans to the suburbs.

In 1980, Killingsworth Street marked the northern edge of the African American neighborhood. Thirty years later, the African American population shifted northwest along Lombard and northeast toward Parkrose. The number of children living in poverty grew in Clark County, in Washington County and especially in Multnomah County east of the I-205. The largest DECREASES in poverty were inside the borders of the city of Portland, in gentrifying neighborhoods.

At the start of the 21st century, Vietnamese residents were most likely to live in east-side neighborhoods, 3 to 6 miles from downtown Portland. Russians, Ukranians, and other immigrants from Eastern Europe also lived in those areas. Koreans and Indians established a presence in Beaverton. Hispanics found affordable housing in aging suburbs like Hillsboro, Forest Grove and Canby. Abbott notes of the ethnic and racial demography of Portland, “The multitude that makes up the life and future of the city now lives towards its edges rather than its center.”

Image credit: Image photographed from Portland in Three Centuries, the Place and the People by Carl Abbott. Original photo by Allan deLay, provided to Abbott by Thomas Robinson.

[…] the so-called ‘Justice’ Center. Portland has its own bitter history of racial violence, segregation, and urban gentrification. Speakers included legendary community organizers Jo Ann Hardesty, Rev. […]