Since I moved here three weeks ago, and even when I visited, I noticed the dirth of ethnic diversity in central Portland and in the close-in neighborhoods. So I decided to investigate why this may be and found a great resource in Carl Abbott’s book, Portland in Three Centuries, the Place and the People, published in 2011.

Below is the story of the nonwhite population of Portland, with an emphasis on the African American story, based on Abbot’s book. I will publish it in two parts. This is part I.

In the 1860s, Portland’s African American population grew from a mere 16 people to 147 due to blacks migrating from the south due to the Civil War. But Portlanders were not very welcoming of this African American population boom. In 1867, the school district and courts refused to black chidren in their all-white schools. Instead, they suggested, $800 could be apportioned towards starting a segregated school that would enroll up to 25 black students over the next 5 years. But the economy took a severe downturn and it became too costly to start this segregated school, so African Americans were grudgingly allowed into the regular schools.

Still, in the late 1800s, the African American population was too small to make a major impression on the city. But it was strong enough to develop its own institutions like the AME Zion Church in 1862 and it held annual celebrations of the Emancipation Proclamation in the years that followed the Civil War.

In the 1910s, housing developers wrote restrictive deeds prohibiting home sales to African Americans and other minorities, including Asians. These discriminatory restrictions were deemed unenforceable by the US Supreme Court in 1948, but were practiced nonetheless for years afterwards.

In the early 1920s, as the Ku Klux Klan was spreading in the South, Midwest and West, it took root in Oregon from Tillamook to La Grande among a largely Protestant community who had seen hard times in the last five years. In 1922, Klan-backed candidates won 2 of 3 seats on the Multnomah County Commission and 12 of 13 county seats in the State legislature. But interest in the Klan eventually waned as people discovered that Klan-backed politicians were just as untrustworthy and unreliable as the people they had replaced.

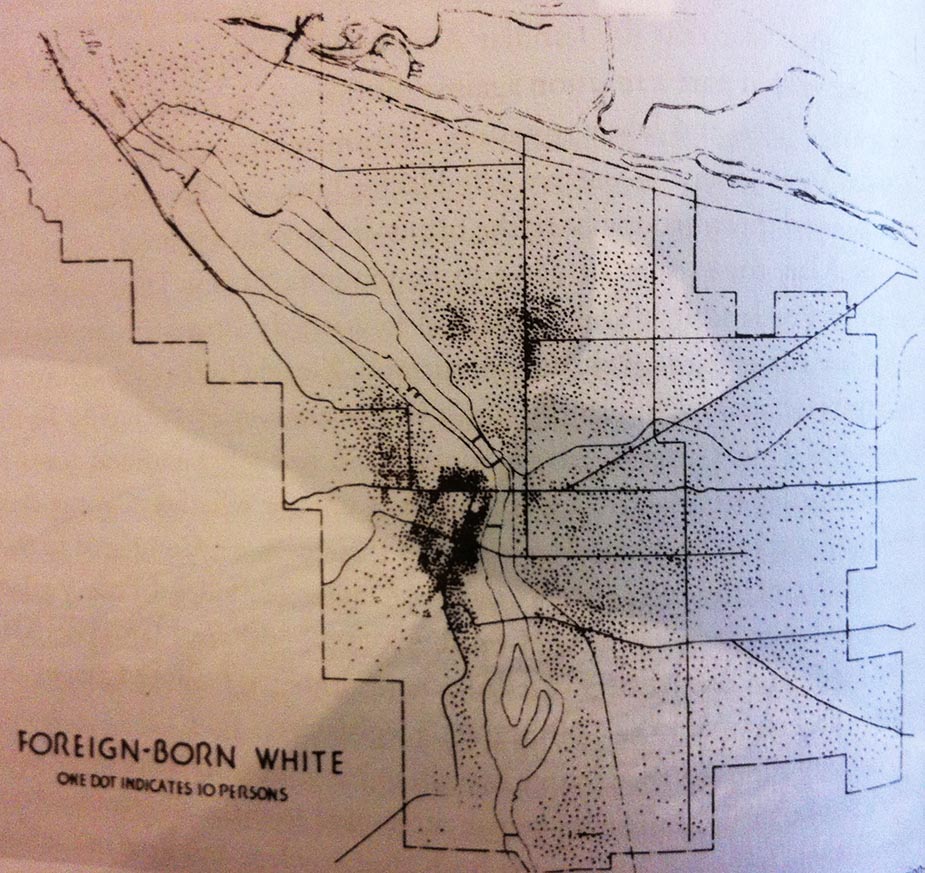

Ironically, Portland’s immigrant neighborhoods were reaching their peak around the same time the Klan had its hold on the city. According to Abbott, “Albina and Brookly, Chinatown and Japantown, Slabtown and South Portland were all neighborhoods where Portlanders from multiple countries and continetns lived, mingled, and sought to launch their children as successful Americans.”

Since the turn of the 20th century, South Portlnad, with its small houses and affordable apartments, had attracted Italians and Jews from Russia and Eastern Europe. Easy access to Downtown made the neighborhodd convenient to newcomers with jobs as construction workers, peddlers and salesmen. Many immigrants worked in the factories and saw mills along the adjacent waterfront. Others ran businesses in the commercial core along First Avenue where streetcars could drop people in from of bakeries, drugstores, Italian groceries, Kosher markets, and theaters showing Italian films.

Immigrant South Portlanders would also peddle goods out of horse-drawn carriages, perhaps the first iteration of modern-day food trucks. Italians often peddled fruits and vegetables. Jewish peddlers sold used household items. Second hand stores would then resell those items bought from those peddlers.

In 1925, the newly constructed Ross Island Bridge took out several blocks for bridge access and poured traffic into South Portland’s streets. This marked a shift in the neighborhood, with many successful immigrant families opting to move to newer homes elsewhere.

The blocks between Burnside and Union Station were even more diverse that South Portland. A 1930 census shows 1,919 people crowded into hotels and apartments, 1,557 of which were single men. A full 25% of these people were Japanese, Chinese or Filipino. Japanese and Chinese businessmen were tailors, barbers, restaurant owners, and operators of hotels and rooming houses. Japanese and Chinese families shared the neighborhood with single men born in Finland, Sweden, Greece, Germany and other countries, including the U.S.

Prosperity during WWI and again in the early 1930s because of the timber industry made it easier for immigrants or their children to move from core neighborhoods to newly built middle-class housing further out. These ethnic migrations opened older parts of Albina, in northeast Portland, to a gradually growing African American population.

Stay tuned to Part II of the story of the ethnic population of Portland coming up next!

Image credit: Image photographed from Portland in Three Centuries, the Place and the People. Original map from Carl Abbott’s collection.