I kept hearing of Pietro Belluschi as a name of an architect I need to know about ever since I moved to Portland. To give you an idea of how prominent and successful this Portland architect became over his fifty years in practice, here is a list of impressive commissions he got: the Equitable Building in Portland, the Portland Art Museum, the Bank of America World Headquarters in San Francisco, and the Julliard School and the Lincoln Center in New York.

I came upon one of his buildings for the first time on a Biking About Architecture tour by Jenny Fosmire. It was the Central Lutheran Church on northeast Hancock Street. Immediately I saw what all the fuss was about. The church has a beautiful understated elegance to it and you would only notice it if you stopped and examined it. Indeed, all of the buildings I have seen of Belluschi’s since have the same understated elegance. They don’t pop out at you on the street, but once you recognize what you’re looking at, you see the quiet beauty radiating from within.

This Sunday I attended a bus tour of Belluschi’s churches called “Understated Elegance” organized by the Architectural Heritage Center and led by architectural historian Eric Wheeler. I have always been interested in sacred spaces, ever since I was in college , so I was excited to see how this famous architect dealt with them. I learned that Belluschi managed to create spaces that feel universally sacred using form, materials and natural daylight and without having to rely on representational imagery.

Above all else, Belluschi valued simplicity in architecture. His son Tony, who is also an architect and was on the tour with us, said his father valued the “simplicity of the saint versus the simplicity of the fool.” Churches can be elaborate concoctions of decoration, representational imagery and lots of ornamentation. But Belluschi tried to retain the sacred essence of the Church while eliminating anything that was superfluous.

The first church we visited was the one I had come upon on the Biking About Architecture tour, the Central Lutheran Church built in 1950. But I had not had a chance to go inside it then. While Belluschi’s churches may be understated from the outside, they are grand and gorgeous and stunning on the inside.

Wheeler, our tour guide, did a wonderful thing. He made sure the lights were off before we entered the church, so we could see the way the natural daylight came into the building as it was an important design element. Belluschi was a master at using daylight to create dramatic spaces and to emphasize certain areas of the church.

At Central Lutheran, for example. Belluschi left the nave relatively dark, with muted light coming in from blue stained glass.

And he dramatically lit the sanctuary with clerestory windows on the back walls of the space that the congregants would never see, to give it an effect of being lit mysteriously, lending to a divine and ethereal feel.

The second church we visited, St. Thomas More Catholic Church on southwest Patton Road, was his very first church commission. It was built ten years earlier, in 1940. It had a very low budget and was likely built by the congregation. Once again, it doesn’t look remarkable from the outside, but inside it’s very beautiful.

The striking thing about this church is its materiality.

The interior is almost entirely clad in regional wood. Though Belluschi was a modernist, he wasn’t a steel and glass modernist, he tempered his modernism by using regional materials.

So in the case of the Pacific Northwest, it meant featuring the variety of woods that are so prevalent here. The extensive use of wood makes for a warm and accessible modern style unique to Belluschi.

He was also the first to use glulam beams in churches. Before Belluschi, glulams were primarily used in warehouse situations, but never in sacred or institutional spaces. Belluschi saw the beauty of glulam beams and incorporated them as a major design element in the most sacred of spaces.

The Zion Lutheran Church on southwest Eighteenth Avenue was the third building we visited and was my very favorite. For me, the composition, proportion, daylighting and procession in this church was perfected. Once again, this church looks like a nondescript brick building if you’re just whizzing by in your car or on your bike. It is only if you stop and look at it that you see some curious details, which give away the grandeur on the interior. For instance, the seemingly random pattern of single glass blocks that perforate the brick wall immediately indicate that this building is special.

These same unassuming glass blocks bring in bursts of light on the interior, making for a sort of mural of daylight on the wall.

The glass blocks are flush with the exterior, creating an inset on the inside, which Belluschi covered with bright metal to enhance the light that comes in.

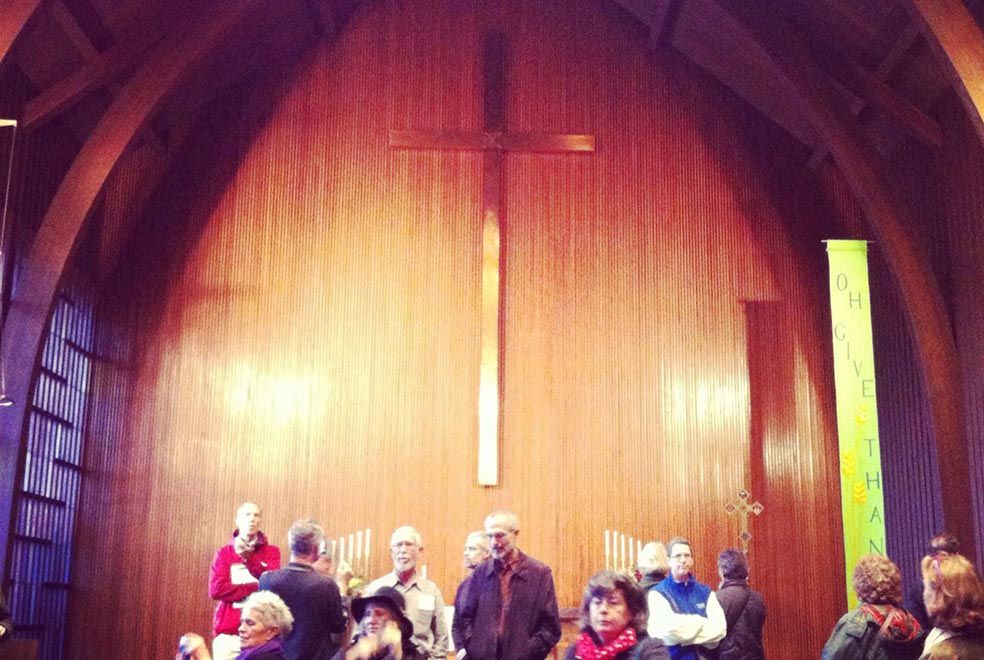

On a grander scale, the gothic glulam arches make for an amazing and breathtaking space. The soft kirf back wall made of local wood lends a warm and beautiful backdrop to the sanctuary and focal point for the congregants.

The final church we visited was the Chapel of Christ the Teacher at the University of Portland built in 1986. I was curious and almost skeptical of what this church would look like because the 1980s weren’t the best years for architecture. But this building was surprisingly elegant and innovative, a testament to Belluschi’s ability to evolve and continue to create good work through changing times. This building, out of all four, was the most interesting from the exterior.

It didn’t stand out so much for its overall form, but for the Japanese-inspired details, including the carved, ornate, but still understated wood columns and the fantastic carved wood door. Both of these elements were designed by artists whom Belluschi hand picked himself.

The interior of the church reflected a change in the way churches have evolved over time. Instead of the altar being held above and made more important than the congregation, the altar was at the same level as the congregation’s seats and was much closer, implying that the priest is much more a part of the congregation than separate from it. Also, this church is cube shaped, which is a more democratic shape than the linear, processional basilica shape of his previous church designs.

Photo Credit: All photos by the author.

Those churches are amazing, nice article.