Today’s post is by contributing writer Jennifer Gunther.

*Don’t miss the panel discussion tomorrow, March 28, as part of Modern Phoenix week, at the Phoenix Art Museum called Perspectives on Frank Lloyd Wright with panelists Grady Gammage, Emily Talen, Vernon Swaback, David Davis and Eric Anderson.*

About one month remains for Phoenix Art Museum visitors to admire and explore the work of American architecture legend Frank Lloyd Wright. “Frank Lloyd Wright: Organic Architecture for the 21st Century” will be on view until April 29.

The name Frank Lloyd Wright appears everywhere in Phoenix. The name of the Wisconsin-native designer who extended his famous Taliesin school to the beautiful Taliesin West campus in Scottsdale is as commonplace in local, casual architectural discussion as it is in design history lectures and textbooks, as well as in practicing firms around the world, where it may be used more critically. A boulevard in Scottsdale bears the name Frank Lloyd Wright, and the architecture section of the Tempe Public Library is almost entirely composed of coffee table books on his most famous works.

Despite the household status of Wright’s name, the true brilliance of his designs may not be apparent to those who are only familiar with his celebrity ─ not to mention those who know a little bit more about his original “starchitect” attitude that blew his accomplishments out of proportion and scandalous romantic history. “Organic Architecture” invites viewers to step past the name and get to know a more intimate part of the designer, at least the part that continues to inspire architects today.

Wright’s strong belief in the relationship between nature and the built environment provides a understated guide through the exhibit, which is organized according to several of his methods of designing for “continuity” (as he called it) between the two environments: interacting with the site and using local materials, integration of pre-fab technology and space efficiency and, finally, his utopian urban planning aspirations. As information on the exhibit’s website says, these sections highlight the idea that Wright’s style has similarities to contemporary focus on sustainability. A warning for visitors, though: these concepts may only be detectable to those who are interested in architecture, sustainability and construction. The exhibit does not address them enough to establish a strong dialogue for visitors who may not be students or professionals and may not know how to look for them.

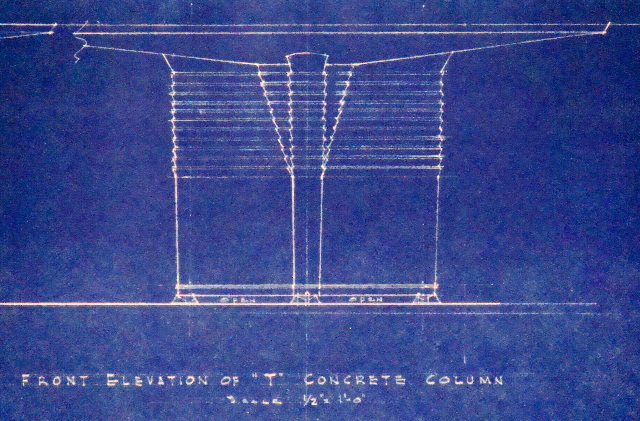

“Organic Architecture” features conceptual models, colorful conceptual renderings and precise technical drawings with elegant block lettering that could easily spur a follow-up exhibit on the dying art of drafting. Fallingwater, the house in Bear Run, Pa., that is situated atop a flowing stream, is showcased through film footage that is projected onto a screen.

Wright’s 1957 “Oasis” model of his vision for the Arizona state capitol building was the first major display that also tied the exhibit to the state centennial. It featured a blue, open geometric shade structure that encompassed the sprawling two to three-story building, which would have been sited in Papago Park. It also rose into a tall spire that held a radio tower. The “Oasis” was developed by Wright out of curiosity (and perhaps to exemplify his trademark narcissism), as it was a pro bono design that never went beyond the modeling stage. The parallels to nature, experimentation and ambition that characterize many of Wright’s designs can be seen in this grand concept that is a lot more interesting than the current capitol building complex.

Looking at the large floor plans and various elevation renderings on display allows the viewer to step into the architect’s mind and experience the iconic Taliesins, Johnson Wax Administration and Robie House buildings as Wright envisioned them. For what may be the first time for many viewers, his design values and intentions precede his reputation when analyzing these meticulous plans. Note, though, that many of the designs on display were conceptual and never made it past the drafting board. They were also drawn by the hands of Taliesin apprentices.

Another warning for visitors is appropriate here: technical documents, which these drawings are, can be boring ─ even to professionals. However, showing the drawings to untrained eyes may be what makes “Organic Architecture” a unique opportunity. Reading these documents encourages the everyday users of buildings to explore what makes Wright’s body of work a fixture in American modernism, and it can let them apply their discoveries and criticisms to other buildings they experience. It is entirely appropriate to pick apart the scale, composition, angles, greenery and materials represented by the drawings, including Wright’s. “Organic Architecture” may thus present visitors a chance to roast a superstar in addition to being in awe of him. The commentary my friends and I came up while walking through the galleries was one of the more interesting First Friday experiences I had with my friends. Of course, it helped that some of us were design students.

Where one may question the significance of Fallingwater’s cantilevered balconies and mold-encouraging placement over running water, one can also begin to see how the walls follow the natural flow of the water in a subtle design that lets the users participate in the natural rhythm, not just admire it. Where the masonry Wright employed in many of his interiors seems rough in comparison to the comfort and ease of the classic smooth walls of most of our interiors, it becomes clear that nature does not stop at the front door for Wright. The fact that the stone walls are frequently outlined by wood strips further echoes natural terrain and landscapes. The hand-drawn masonry of several of his plans contrast with the comfort and support that are represented by his space-saving built-in furniture designs to create an interesting indoor experience. With Wright, after all, even the furniture placement made a profound design statement (or testament to his absolute mastery of design). In a rendering of an indoor-outdoor space, it seemed as though boulders were just another couple enjoying the view ─ just like they do in nature.

One of the most enjoyable parts of the drawings were the edges where apprentices drew green ovals and scribbled them in to denote sylvan landscapes that continued beyond the site. Seeing their freehand notes and test shapes they played with before buckling down and charting the low roofs that capture Wright’s love of the Midwest plains offered an honest perspective. Looking at the very beginning of Wright’s concepts is one of a kind and inspires viewers to re-examine what they know about Wright, even what they know about architecture.

Wright’s Broadacre model of an organic city plan put his ideals on a much larger scale and embraced the freedom of the automobile. The pockets of trees and the focus on spreading the city across the landscape expressed how much Wright valued the presence of nature in city life, though it is true the distance between the houses and commercial centers ignored the realities of the environmental costs of fossil fuel use, the health effects of car dependency, cars’ dominating influence on urban design and sprawl issues we know too well in current-day Phoenix.

What makes Wright’s organic style so attractive to us is the simple understanding that architecture dialogues with nature. Though he may not have been the first designer to pay more attention to the possibilities of trees, rocks and water informing buildings in an era that preferred turning to emerging technology and mechanical innovation for inspiration, he did it in a way that brought renewed interest in architecture. Wright’s fame, whether most of it is ill-deserved, can serve as a sign that this type of design resonates with something deep inside of us and is not a trend developed by elite or contemporary designers. “Organic Architecture” begins to break down Wright’s legacy for visitors, revealing the genius of the organic aesthetic that is not exclusively Wright’s forte.

Photo Credit: An original blueprint of Wright’s Johnson Wax Building in Racine, WI. Photo from PrairieMod.

I sure hope one day our State is wise enough to revisit FLWs vision for our State Capitol. While Papago Park is not an appropriate site and it would be silly to abandon the current Capitol Mall, I do think “Oasis” could likely be built over by 19th Ave. The Executive Tower is a monstrosity, and the House & Senate buildings need to be demolished and their original gardens brought back.

I’d love to see “Oasis” built facing 19th Ave, behind the historic Statehouse. Directly across the Street could be a multi modal transit hub for the LRT, Commuter Rail, Circulators & City Buses.

Great counterpoint to the recent Phoenix New Times article which completely missed the reason for the show. 🙂