Today’s post is a glimpse into the world of a first year architecture student by contributing writer Jennifer Gunther.

Jennifer Gunther is a design management sophomore at Arizona State University. She has written for NAU’s The Lumberjack and ASU’s own State Press, as well as for Modern Phoenix. Though she may prefer writing to drawing, architecture school will probably always loom over her future.

If I could describe my first semester of architecture school in one word, I would use the adjective that was on everyone’s lips in the studio: intense.

The unique lessons of craftsmanship and spatial relationship that I learned this semester made the blood, sweat, tears and even vomit-caliber intensity worthwhile. At the same time, the competitive nature of the program frequently – and sometimes literally – crowded out the educational aspect of my design formation.

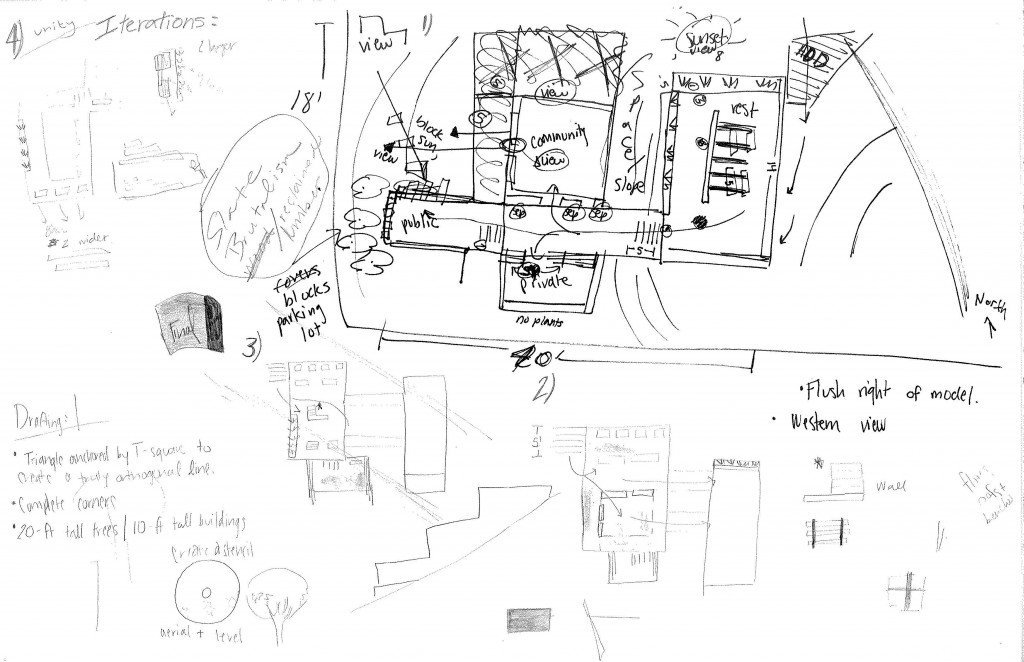

Many students, like me, enroll in architecture programs expecting one thing and discovering another. I overheard students who were surprised that we were making collages and taking photos the first few weeks and were impatient to start doing “actual” architectural work by building models. I spoke to one student who was anticipating more math and physics classes than assignments like our compositions of black squares. I struggled daily with making a connection between the technicality of drawing plans and building models and the theoretical components of the design process. My 300 peers and I often complained to each other about workloads that were difficult to manage with minimal face time with the instructors we easily outnumbered.

One major thing I learned this semester is that it is obvious that architecture is inspiring. Most of us admire what we recognize as excellent design, and a good amount of us pursue it as a career. In fact, some of us have wanted to be landscape architects ever since the afternoons we spent playing in the sandbox as children. But we might not know exactly why we admire the Eiffel Tower, Fallingwater or the Sydney Opera House, and we might not know what exactly it is we’re studying in a crowded lecture hall or on a drafting board late at night.

This nebulosity can make it easy to define architectural design as a sexy, expensive building – you know the ones I’m talking about. I saw some projects at pin-ups that followed these attractive structures’ suit.

Architecture can also become an esoteric vocation that only someone with a “gift” for design is initiated into. These perceptions could not be further from architectural design’s humble, yet complex identity as a thoughtful response to the form of nature and the needs and desires of people.

Architecture is relevant to everyone because the creativity required to come up with a solution is an inherently human trait. How a building is built, how it is used and how it interacts with surrounding buildings, the greater urban fabric and the environment affects everyone who experiences a city and must therefore be understood at appropriate levels by everyone within the city.

Trendiness and pretentiousness are not necessarily parts of a formula of looking at a situation (also termed as a problem) through multiple perspectives and coming up with the best plan or solution for a specific goal, given all possible variables and constraints.

There must be more dialogue on the subject of architecture itself, and there must be more public awareness of architecture’s role in our lives.

To achieve this, educators must continue to devote themselves to instilling a sense of architecture’s reach into the community by emphasizing the students’ future role in catalyzing this significance. In other words, students must not look forward to building cool models, but to learning how to build models whose beauty comes from their design’s substance. This requires equal amounts of active studio work and reflection on theory. Constant feedback and discussion is essential. Sleep would also be appreciated so we can completely absorb all this learning.

Practitioners should continue to innovate their craft and engage the public they serve in one way or another in their designs through media and advocacy.

Knowing what exactly successful or good architectural design is and why it is essential is becoming a crucial topic for today’s movers and shakers outside the field, be they engineers, business executives or lawmakers, as the world becomes more and more urban. Public interest will be whetted beyond looking at pictures of cutting-edge structures in magazines and on blogs as this relevance increases.

Architecture school should thus ideally be described as a nexus of passion rather than simply being intense. This passion should spread beyond the studio and into the larger community so everyone can be aware of a successful building’s key elements and be able to recognize it in any building, not the hottest new project by the latest “starchitect.”

Let’s start building on this all-inclusive conversation.