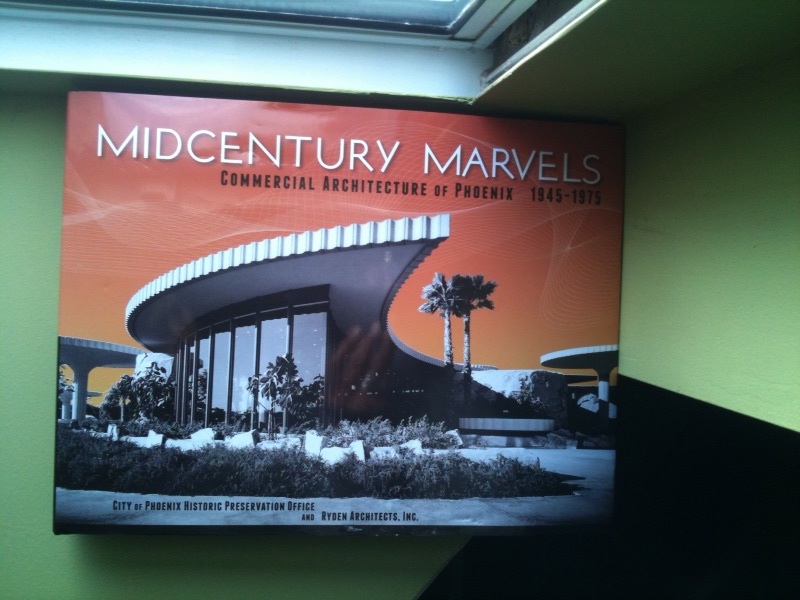

Today’s post is the second half of my conversation with local historic preservation architect Don Ryden and the author of Midcentury Marvels. If you missed part I, don’t forget to go back and take a look!

Today’s post is the second half of my conversation with local historic preservation architect Don Ryden and the author of Midcentury Marvels. If you missed part I, don’t forget to go back and take a look!

Blooming Rock: You had mentioned the idea of communal memory at your lecture for the release of Midcentury Marvels at the Phoenix Council Chambers. Can you talk a little bit about this concept?

Don Ryden: Communal memory is one of the reasons we deal with historic preservation. In the lecture I said it’s either love, money, or duty (why we preserve historic buildings). Communal memory is more in the love aspect because as we pointed out in the “Marvel”ous book, we had visionaries grow up in our town and see the opportunity after World War II to make something totally new. And they brought with them these visions, they brought with them optimism, a key word here, their determination to make a go of it. It was a completely new world after the war with completely new opportunities afforded by government assitance through FHA and GI Bill and things like that, so they could get started with a whole new life. With these aspects of optimism, they designed and built their dreams. They were building for you and me, their city for our future. So that’s why I call Phoenix a City of Optimism and the buildings here the Architecture of Opportunities. So the vision and the values that they have are embodied in the design of those buildings.

We as young people or just as newcomers, interact with these buildings and have had experiences that we remember, good, bad or indifferent. Usually good, as evidenced by people who really love going to Legend City or love to eat at Green Gables Restaurant or things like that. The communal memory (is) like my example of the Ladmo Bag, that I whipped out in front of the crowd (at the release of Midcentury Marvels). Fifty percent of the group knew what I had in my hand. The other half was either too young or was from out of town and didn’t know that this was a communal memory jogger. The Ladmo Bag is about as near and dear, as happy an icon of childhood in Phoenix as anyone could ever imagine. And so, you have an association with that as a good thing happening as a child. And each person in that room could tell you a story about their Ladmo Bag or the fact that they didn’t get one, as a communal memory. Taking it all together. Fifty percent of the people in that room could talk to each other and get it or, turn to the person who wasn’t in (on it) and explain to them what a Ladmo bag is or what did it mean to go to Legend City to watch the Wallace and Ladmo stage show or go to the KPHO building to see the TV show. So, the values and the experiences that thousands and thousands of 1960s kids had together is the communal memory of the city. By preserving your Ladmo bag, or better yet, preserving a Legend City of a Green Gables, or a Bill Johnson’s Big Apple or whatever the building is, it fosters the perpetuation of not only the memory, but more importantly the values of the community.

By having such huge growth in Phoenix, people came to town with values from different places. Not that they were bad, they were different. Even today I run in to people from the East Coast who look around here and say, you’ve got nothing worth looking at. We have all this history from the founding of America. And I go, good for you! We have history of the founding of Phoenix! Tune in with me in 200 years and we’ll see what it means. It has to do with perspective. So communal memory preserves the buildings, by preserving the buildings you then preserve the trigger that retells the stories of vision and values. When you don’t have these triggers as you drive your children through town and tell them the stories that they get tired of, well, we start to lose sight of what our communal values and visions are. And that’s why it’s important to preserve the best of the best buildings. You can’t keep them all and they’re not all worth keeping. But the best of the best really should be kept so as to complete the circle of life and inspire vision and values in those who come after us. That’s the circle.

Blooming Rock: So do plan to write more books about Phoenix architecture?

Don Ryden: I would really like to do a companion volume, or two or three, for Midcentury Marvels Commercial Architecture. The next one that should be done, that would make the most difference would be Midcentury Houses. We have huge numbers of them and everyone lives in a house of some sort, even if it’s a garden apartment. There’s another building type. Residential is a whole different story. Between the commercial gems and both high style and humble houses of the 50s and 60s and the 70s, those would make the most difference if people understood why they shouldn’t be stuccoing their ranch houses of concrete block or brick, and putting popped out styrofoam frames and changing the steel casement windows out for aluminum sliders and and and…It’s just destroying the cohesive character of their neighborhoods and really kind of breaking that cycle of vision.

So too I think it’s important to look at houses in a different scale as before the War. We’re here in the Encanto Palmcroft neighborhood where they’re all custom houses in period revival style. So you look at house by house by house, almost any of them could be nominated (for the historical register) individually for architectural “niftyness”. But what happens when you get to tract homes? There’s a whole new way of looking at them. Not house by house. The unit is not the house, the unit is the subdivision. And it isn’t that there’s three floor plans and two elevations over and over and over again in different permutations in the neighborhood. Is that anything? No. You don’t nominate a tract neighborhood for architecture. You nominate it for community planning and development or for the design and concept of developing planning of a neighborhood – wiggly streets and cul-de-sacs instead of grid. You see what I mean? I can do a lecture on that for another hour or two.

We have to help people understand that after the war, the scale of time and space expanded ten-fold. It was no longer a streetcar city. It became the family automobile city. The buses couldn’t even keep up with it. So that would be the next book because that would make a difference to people. And then finally you could do a book on Midcentury Miracles which would be houses of worship. Those are as wild and crazy and wonderful as some of the commercial architecture. And you could put into that more institutional things like government buildings, schools, that sort of a thing could easily be a volume in itself.

But the question was am I planning on writing a new one? No one’s asked. And in these troubled times, it’s tough enough to keep the family fed and if I did another one I couldn’t possibly begin one as a hobby, even though Midcentury Marvels turned into half of a hobby. So yeah, if somebody could figure out how to put the funding together and finance the production of it, (yes). Now, having the experience of this volume, we would be able to streamline the process. I guess experience is nothing but surviving a miserable series of mistakes. So we have experience and happily so. I think we can count it as something we’re all very proud of and I think that we have made a difference in our community by being able to publish it. I hope certainly that they can find the funding to have a second edition. I was told last night by Barbara Stocklin (City of Phoenix Historic Preservation Officer) that she estimates that they have now sold one-third of their stock, 1500 books. So they have sold 500 books in three weeks. Now of course there is a big wave right now and it’ll taper off. But to get rid of a third of them in three weeks, yeah that’s pretty good. They’re having trouble figuring out where in the world they’re going to find more money, especially in the City Council to be able to go for a second edition. And with that there’s a few little things we’d like to change, everyone has that opportunity. I mean there’s nothing in there that I regret, but there’re some things that we could tune up and improve. That’s kind of where it stands with that thing. Our big push right now is the step two, this is the launch pad, now what do we do? We’ve got to get, as Barbara (Stocklin) said, designation.

Blooming Rock: What do you do as a historic preservation architect? What are the wide variety of services you perform?

Don Ryden: Well, there are many people who claim to be historic preservation architects. Yet the realm of what you can do as a preservation architect, or in the federal terminology, historical architect, is so wide as to encompass planning at a wide scale, entire towns, communities or neighborhoods, dealing with individual buildings, dealing with individual rooms, dealing with individual features like a fire place, or a window or an archway and conserving the materials in a building. You can deal with surveying historic neighborhoods or towns, to determine historic district. When I say survey, it’s not like a land survey with a transit and a rod. It’s cameras and clipboards, looking for the significance and integrity of each component of a neighborhood. You then determine what its boundary is and you can go to the next step which is designation or the writing of a national register nomination.

Following on that you help people to get their tax credits. If it’s a commercial building you can help them get their IRS tax credits, you can assist them in getting property tax reductions, you help them write grant applications, you can then do feasibility studies for historic buildings. You do historic building preservation plans. I’m doing one right now for the State Capitol. We’ve done that for things like the adobe arsenal on 56th St. and McDowell for the National Guard. We’ve done them for all kinds of things like that. You can do interpretive plans for museums, write the story, design the exhibits, invent how you have people tour through historic period houses, where do you start, where do you end? How do you tell the story? What’s the take home information for the people? We do renderings of befores and afters, that kind of thing.

You deal with sustainability. Here I sit in a 1920s adobe house which tells you all kinds of lessons about how to build comfortably in the desert before even swamp coolers were built. This (building) was built in 1929, swamp coolers were invented in 1930 and didn’t really come on the market until 1933 and 35. So this house I could go through and give you the demonstration of sustainability solutions built into vernacular architecture. We study vernacular architecture with archeologists, whether it’s prehistoric or even historic, lying down or standing up. We deal with archeologists, we deal with historians. We’re always dealing with multi-disciplinary collaborations, usually with historians, archeologists, engineers, surveyors, photographers and other architects. I work as much as a consultant to what we always say, the “real” architects, the “real world architects” as I do working on my own design of new things and doing preservation projects. You go out and lecture and teach and talk to students, talk to community groups, design new buildings, design compatible new buildings with the old, you turn old buildings into new, you deal with the structural and systems engineers. There’s just no end to all the things you can do or deal with. And it touches every aspect of “real world” architecture, but it’s harder and harder and harder than just building new buildings. I’m too dumb to realize that what I do is almost impossible.

Photo Credit: Don Ryden’s book Midcentury Marvels. Photo by the author.

I just picked up a copy of the book and can’t wait to look through it.

cool Jacob!