About a year ago, I was asked to be a part of a cohousing effort here in Phoenix and everything that I learned about community-oriented design inspired me tremendously and has informed much of my thinking about neighborhoods and our city. Cohousing is a very specific model of community living that was originally created in Denmark. A cohousing community usually consists of around 12 to 36 units, is designed by a participatory process led by future residents, has extensive common facilities usually in the form of a common house and is ultimately managed by its residents.

About a year ago, I was asked to be a part of a cohousing effort here in Phoenix and everything that I learned about community-oriented design inspired me tremendously and has informed much of my thinking about neighborhoods and our city. Cohousing is a very specific model of community living that was originally created in Denmark. A cohousing community usually consists of around 12 to 36 units, is designed by a participatory process led by future residents, has extensive common facilities usually in the form of a common house and is ultimately managed by its residents.

But there are some universal community-building design principles that are used in cohousing that translate into many other types of developments, such small multi-family housing that I wrote about yesterday, or public spaces like plazas or parks, some retail environments, entire neighborhoods, and even entire cities!

These universal principles are what I want to share with you today:

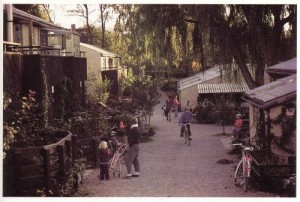

The first is centralized circulation. Centralized circulation means providing a main pedestrian path in the development, like a main street. This main street affords opportunities to run into your neighbors and strike up conversations. When there are too many paths that go to the individual homes, there isn’t enough use of any one path to ensure that you will meet your neighbors on it. The idea behind centralized circulation is to provide an opportunity for community life to unfold outside of the individual units.

The second universal principle of community-oriented design is the clustering of homes as opposed to detached single family houses. The clustering of homes “uses land, energy and materials more economically than detached houses and…also supports more efficient forms of mass transit” according to Charles Durrett, the premier authority on cohousing in the States in his book Senior Cohousing, A Community Approach to Independent Living Handbook. The clustering of homes provides not only community benefits such as the opportunity for larger open spaces for things like community gardens, but it retains a lot of the benefits of single family housing such as private access to individual homes and private gardens.

A third principle is easy access to outdoor spaces that accommodates people of differing abilities. This is especially important in senior communities, but also applies to multi-generational ones. Durrett says that accessibility to the outdoors is just as important as the interior accessibility in buildings.

The reason access to outdoor spaces is so important in community-oriented design is because another principle of this kind of design is the fact that outdoor spaces contribute to the quality of life just as much as the buildings do. According to Durrett, “outdoor spaces can be used for sitting, pedestrian traffic, spontaneous encounters, gardening, and socializing.”

A mainstay of community-oriented design is that it creates a living place without cars. All community-oriented developments are pedestrian-oriented and parking is relegated to the periphery. Durrett believes that “Car-free pedestrian lanes and courts are essential to creating places where everyone can move about relaxed and worry-free.” He says that clustering the parking also frees up buildings to be oriented according to the sun, the people or the terrain and not so much in service of having a car or several cars parked in front of each unit. A fringe benefit of clustering parking is that this also fosters chance encounters with others going to the same place to pick up their car and it’s another opportunity to interact with people in the community. Plus community-oriented design usually ends up reducing the required parking spaces per unit. This happens when say for example a family needs another car, they might likely opt to share one with another household in the community.

What Durrett and others have found in their research and experience is that placing cars close to houses kills community. He asserts that “the people-contact between the buildings drop many, many fold when parking areas are placed adjacent to the houses. As a direct result, community, physical, and emotional health deteriorates.”

As I mentioned earlier, an integral part of cohosing is the common house. One of the interesting things about the common house is the impact of its location on the community. According to Durrett, the residents must pass the common house on their way home, the common house should be visible from each house and the common house must be equidistant from all the dwellings. These very specific and thoughtful requirements are what optimize community and use of the common facilities.

Another well-thought out aspect of community-oriented design is concept of transitional spaces. These are the transitions between the private dwellings, to the community plazas to the public realm. If these transitions are well designed, they will support community life and the relationships among people. But if they’re not, there will be “missing links and fewer opportunities to continue the relationships that keep a group of houses a community. The omission of any of them makes the appropriate use of spaces ambiguous, inhibiting people’s activities” says Durrett. There are many ways to demarcate these transitions physically, but they don’t have to be extreme, they can be as subtle as a change in ground cover. Another example of a graceful transition between public and private is a “soft edge”, a semi-private area or garden between the front of the private dwelling and the common area that increases opportunity for casual socializing.

An important but subtle principle of community-oriented design is visual access. For example, the kitchen/dining area is the room where most people don’t mind being seen in so it can be placed in front of the house near the open community spaces. Durrett explains, “A door and a window connecting the private kitchen to the common area allows a resident to call out to a passing neighbor. Visual access to the common areas, whether indoors or outdoors, allows people to see activities they may want to join.”

And lastly, the concept of gathering nodes defines community-oriented design. For example, on that main pedestrian path I mentioned earlier, there could be picnic tables placed where neighbors can gather for tea or just sit and have a conversation. Ideally, these picnic tables would have a view of the common house to provide that visual access that is integral to community-oriented design. Another example of gathering nodes is clustering things like mailboxes or bicycle racks in strategic places to encourage chance interactions. Gathering nodes can also be easily created with stopping or resting places like benches and tables, or even low walls or steps where people will sit together. A more formal gathering node in the community is often the community plaza, which is usually right outside of the common house and is considered the “community’s front porch”.

As you can see, all of these design concepts have been time-tested and have been refined to optimize community development in cohousing. But I believe they can actually be applied to many different situations one of which is urban planning in general. Imagine if, for example, our Downtown were built around these community-oriented design principles!

Photo Credit: The main pedestrian path in a cohousing development in Trudeslund, Denmark. Photo from Land Plan Australia.

Id love to see a future development in Downtown Phx built with many of these principals in mind for the Seniors who are currently in the Westward Ho. Then of course Id love to see the Ho reverted to use as a nice hotel. It seems to me a rather old building built long before the ADA can’t be the best place for often disabled Seniors, and something designed specifically for them might be better.

Will, agreed! The Westward Ho should be a boutique hotel and is currently way underutilized as subsidized senior housing. I had the privilege of getting a tour not too long ago and it’s stunning inside and has a wonderful pool/courtyard. It is a landmark that needs to be optimized for sure.

Did a resident named Earl or something like that give you a tour? I took my folks on a tour with him for my Moms b-day a few years back, it was really neat, the guy knew a ton about the building and was very nice.

No it was a stuffy ornery building manager who gave the tour. Yours sounds much nicer.